Vertical Forests in Urban Skies

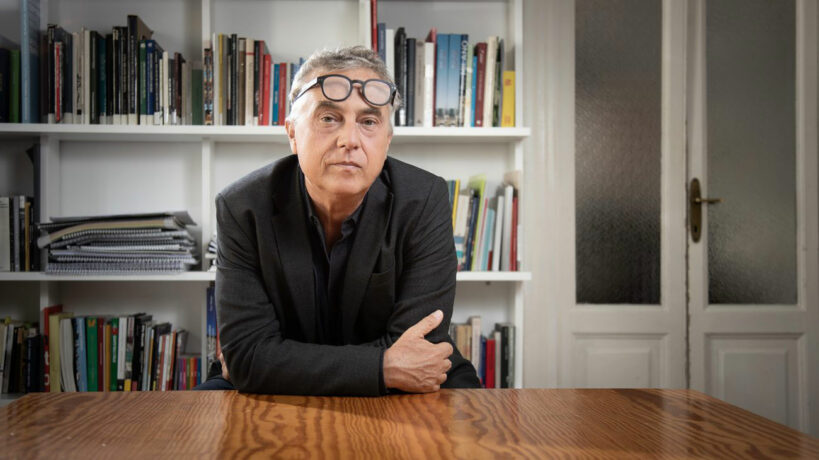

Who is Stefano Boeril?

Milan-born and based architect and urban planner, Stefano Boeri (b.1956) has his degrees from The Polytechnic University of Milan and IUAV University of Venice. The architect set up Boeri Studio in 1999 with Gianandrea Barreca and Giovanni La Varra, and in 2009, the practice was reformed into Stefano Boeri Architetti. Boeri was the editor-in-chief of Domus (2004-07) and Abitare (2007-11), and Head of Culture, Design and Fashion for the city of Milan from 2011 to 2013. The architect’s most emblematic and celebrated project is Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) – two residential towers of 26 and 18 stories in Porta Nuova district of Milan. Built in 2014, the towers feature 800 trees and 20,000 shrubs and perennial plants of more than 90 species, which is an equivalent of 30,000 square meters of woodland occupying 3,000 square meters of urban surface. T

I aim to bring more trees to the city and more humans to the forest“

he vegetation helps mitigate smog and produce oxygen, as well as moderate interior temperatures in the winter and summer by shading the interiors from the sun and blocking harsh winds. The plants also protect the residents from noise pollution and dust from street-level traffic. In 2015, Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) Awards Jury selected Bosco Verticale as that year overall “Best Tall Building Worldwide” and it has served as a prototype for Boeri to design similar structures in Albania, Italy, France, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Egypt, and China. This year, he has been announced as the curator of the comeback edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, to be held from September 5-10, 2021. I visited Stefano Boeri at his studio in Milan in late May; the following is a condensed version of our conversation.

Bosco Verticale

The Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) is a complex of two residential skyscrapers designed by Boeri Studio (Stefano Boeri, Gianandrea Barreca, and Giovanni La Varra) and located in the Porta Nuova district of Milan, Italy. They have a height of 116 metres (381 ft) and 84 m (276 ft) and within the complex is an 11-storey office building.

The distinctive feature of the skyscrapers, both inaugurated in 2014, is the presence of over ninety plant species, including tall shrubs and trees, distributed on the facades. It is an ambitious project of metropolitan reforestation that aims to increase the biodiversity of plant and animal species in the Lombard capital through vertical greening, reducing urban sprawl and contributing to the mitigation of the microclimate.

The Bosco Verticale has received recognition in the architectural community, winning numerous awards. In addition to the International Highrise Award in 2014, it was acknowledged by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat as the “most beautiful and innovative skyscraper in the world” in 2015 and as one of the “fifty most iconic skyscrapers in the world” in 2019. The prototype of the Milanese project will be replicated in other cities.

Q / A

Can we start with one question that you enjoy responding to the most?

That would be the following – How will the role of architecture and architects change in the future? But the answer is more complex. We need to be, on the one hand, open to very specific expectations of our clients and society. And, on the other hand, we need to search for our own unique visions of a room, a building, a neighbourhood, or an entire city. In a way, we need to be able to think very specifically and very broadly at the same time. Ideally, these both attitudes should act simultaneously. And we can’t avoid the pressure of our changing times. The pandemic did not change our reality, but it accelerated how it is being changed. So, we need to be very specific and yet, be able to stand back and address issues on all scales.

Your mother, Cini Boeri [1924-2020] was an important designer and architect. Was she the reason you chose to go into architecture?

No! It was exactly the opposite and I did everything I could to avoid it (laughs). I only decided to go into architecture after I exhausted exploring some other possibilities and failed to succeed (laughs). I was attracted to studying oceanography and marine biology but the best schools to pursue that were in the United States, and at that moment I preferred to stay here. But, in any case, the reason I wanted to keep a distance from architecture was a very strong character of my mother. And even when I decided – Ok, I will go into architecture – I chose to study urbanism, again, to keep some distance from architecture, meaning, designing buildings as objects. First, I went to Milan Polytechnic and then I pursued my PhD in Urban studies at IUAV University of Venice under Aldo Rossi and Vittorio Gregotti. So, that was an attempt to enter the profession of architecture from the perspective of an urbanist. Again, to distance myself from my mother who was a pure designer of products and buildings. And then, of course, we reunited professionally and collaborated on many projects together.

Who would you name among your professors or other figures who you learned from the most, professionally?

There would be many but let me focus on three. First, I would name Giancarlo De Carlo, who was a major influence as my professor at Politecnico di Milano. He was among the original members of TEAM X, together with Alison and Peter Smithson, Aldo van Eyck, and Jacob Bakema who criticised dogmatic and purely aesthetical principles of Le Corbusier. They shifted the profession’s attention to the importance of context, climate, and social agenda. Giancarlo was instrumental in helping me to start teaching – initially, in Genoa where he was from. He also helped me when I was the editor-in-chief of Domus, which was already at the very end of his life.

The second person would be Bernardo Secchi, who was one of the first urbanists who studied the phenomenon of sprawl and dispersion of urban environment in Europe. He also wrote extensively on democratisation of urban space. And the third person, who I would credit, as far as my development as an architect, would be Rem Koolhaas, who is a friend. So, Giancarlo was born in 1919, Bernardo – in 1934, and Rem – in 1944. We have only 12 years difference, so it is a very different relationship. I first met Rem in the 1990s. I think he embodies very well these two extreme qualities I mentioned in the beginning – the capacity to ask important questions and to focus on specific design solutions. I also like his directness and purity of his designs, something I may never reach in my own practice.

Let’s talk about Bosco Verticale. You said that the idea of a tower completely surrounded by threes came in 2007. Was that a radical change in your work? There were no trees in your architecture before that moment, right?

You know, it is not that rare in our profession to have an obsession that you cultivate and develop in anticipation of one day expressing it fully. I was lucky to be able to transform this obsession into a reality. Well, I had my obsession with trees since I was a kid. I tried to bring them into my architecture before but never succeeded before this project. I also did some competition projects with trees.

In 2007, my studio proposed Metrobosco, a green belt of about 30,000 hectares of woods, parks, and avenues with three million trees around Milan. The idea was not only to fight pollution but also to limit urban expansion. But the first real opportunity came with Bosco Verticale. As far as the most immediate inspiration, that came from Italo Calvino, and particularly, his novel The Baron in the Trees, in which a young baron abandons his noble family, climbs the trees and vows never to set foot on the earth again. It is in the trees that he starts making friends, he then falls in love, and so on. The entire novel is about a life in the trees. It is a fantasy, of course. What I like about it is that what is plausible can become possible – this idea of observing the world through the filter of the leaves and branches. That’s the image I had while working on Bosco Verticale. That has become real – people who live there see the world through the filter of the leaves and branches.

I like your description of Bosco Verticale, “A house for trees and birds, inhabited also by humans.” That flips the argument, meaning you don’t view these trees as mere décor, right? The house is really for them, not for us.

Absolutely, the idea was to build a tower for trees – which, incidentally, housed human beings. You really need to experience it in person – to see the city through the leaves of these amazing trees.

The building was completed a while back. Were there any surprises? What lessons did you learn from this project? Because suddenly, there was a kind of the Bosco Verticale effect and the whole world seemed to want it in their city. Was the experience mostly a positive? Nothing went wrong? For example, there is criticism of the excessive use of water, and so on.

Sure, there were many issues and many lessons. The point is that it is an experiment. We are learning as we go. And you are right, we are now completing similar projects in China and now we are just about to open a new building in Eindhoven in the Netherlands, which is a social housing.

So, we are trying to lower the cost of construction of such buildings by relying more on prefabrication and incorporating timber as structural components. Not only these materials and techniques are more economical, but they consume a lot less CO2. And then we work on lowering the cost of maintenance. For example, in Bosco Verticale, you can see the cranes at the top that were originally installed to perform the maintenance of the trees and plants. But it proved to be quite expensive and a couple of years later we started working with arborists who are also climbers. Now we entirely rely on them, which cut the maintenance cost significantly.

Now the cranes are only used if a tree dies and it needs to be replaced. And everything is centralised. In the beginning we were hoping that every tenant would take care of their plants. That did not work and now all the maintenance is done professionally. In fact, the tenants are not allowed to interfere and simply observe how the professionals take care of the plants. It is all curated.

See more / content via: https://www.stirworld.com