The Artist Who Shaped Brazil

About Marx’s Life & Career

In a 2010 interview, the long-time editor of Landscape Architecture Magazine Grady Clay was asked to describe some of landscape architecture’s greatest players of the 20th century. Clay said this about the Brazilian Modernist Roberto Burle Marx: ‘He was big physically and had a huge voice. He sang at parties. He could be heard in the back row no matter what he said.’ Clay was right. Burle Marx certainly knew how to throw a party – his dinners at his experimental nursery and garden estate in Guaratiba, on the western fringes of Rio de Janeiro, were legendary – more importantly, he knew how to make his voice heard.

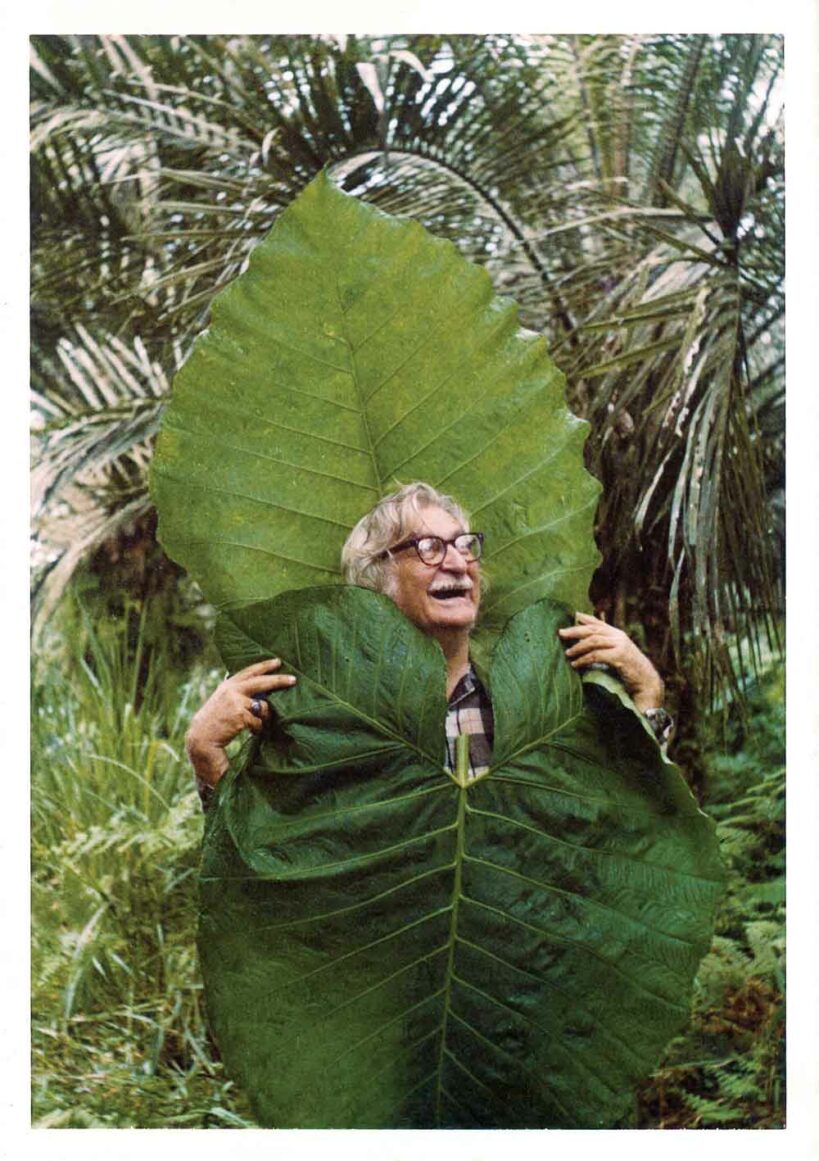

The 150-acre (60-hectare) estate, Sítio Santo Antônio da Bica, was host to such international luminaries as Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, Margaret Mee and Elizabeth Bishop, but more importantly, it was home to Burle Marx’s extraordinary botanical collection of over 3,500 species of tropical plants collected from around Brazil. Purchased with his brother Guilherme Siegfried Burle Marx in 1949, the nursery would become his lifelong project, the nexus of his plant-collecting excursions throughout the various geographic regions of Brazil. Thirty-seven previously unidentified species were discovered on these ‘viagensde coleta’, and their scientific botanical names now include his Latinised name, ‘burle marxii’.

One may even think of a plant as a note. Played in one chord, it will sound in a particular way; in another chord, its value will be altered. It can be legato, staccato, loud or soft, played on a tuba or on a violin. But it is the same note”

In addition to numerous private gardens, Burle Marx designed an astonishing number of public parks and plazas during his long professional career. Shortly after studying painting at the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, a 24-year-old Burle Marx landed in Recife, capital of the north-eastern state of Pernambuco, and renovated a series of municipal plazas. These were his first experiments in ecologically composed gardens, veritable tropical tableaux with plants selected from specific ecoregions of Brazil.

More About Marx’s Projects

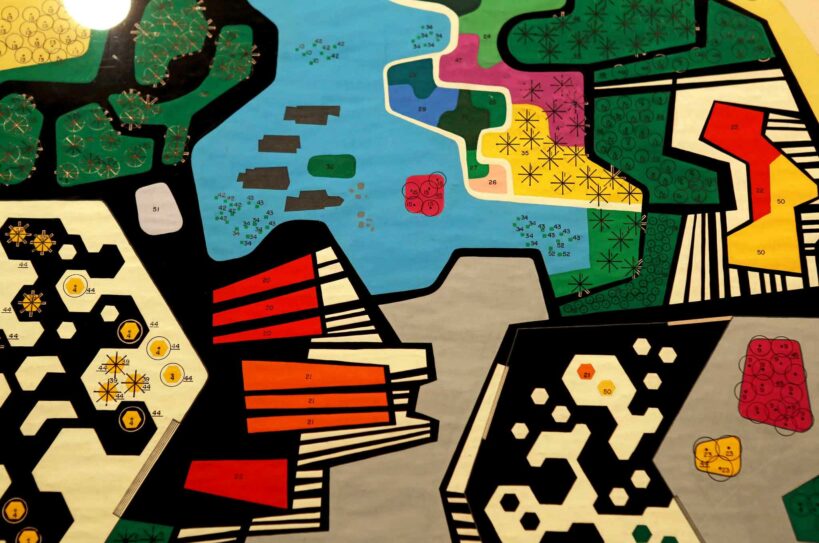

The gardens of the Praça de Casa Forte (1935) deploy aquatic plants from the Amazon in geometric reflecting pools, while the Praça Euclides da Cunha (1934) presents an elliptical cactarium garden, an aestheticised composition of xerophytic plants from the sertão, the dry desert interior of north-eastern Brazil. The narrative power of these tropical plantings serves to express ‘Brazilian-ness’, celebrating biodiversity as a key element of Brazil’s modernity.

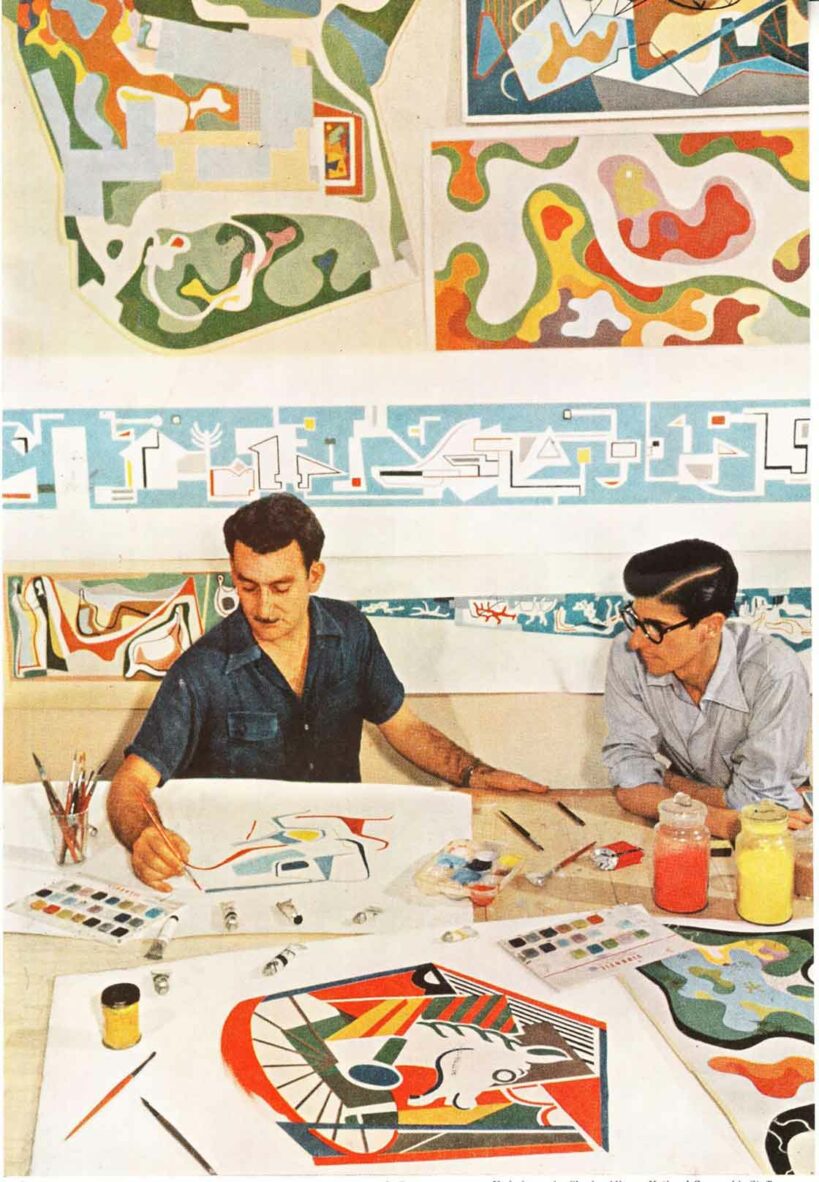

Returning to Rio in 1937, Burle Marx collaborated with Lúcio Costa and his team of young Brazilian architects, designing the public plaza and private roof terraces of the famed Ministry of Education and Health building. This was the headquarters of a government ministry established in the early 1930s by Getúlio Vargas, the technocratic revolutionary president. Burle Marx’s fantastic 1938 amoeboid gouache plan of the minister’s roof garden, with its sinuous forms and bright, flat colours, is evocative of the 19th-century garden plans of Rio’s imperial landscape designer, the Frenchman Auguste François Marie Glaziou and his protégé Paul Villon. Though emblematic of Burle Marx’s work, these amoebas, lush with tropical species, reflect a cultural embrace and a reinterpretation of the European colonial presence in the capital.

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Burle Marx designed large public parks in Belo Horizonte, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, collaborating with an impressive roster of Brazilian architects. In 1943, Oscar Niemeyer invited Burle Marx to design the gardens for his new complex of social and cultural buildings arrayed around an artificial lake at Pampulha, a new garden suburb north of Belo Horizonte. The result was a splendid example of the plastic integration of modern architecture and landscape. This would be followed in 1953 with Burle Marx’s 14 brilliant but unrealised ornamental gardens complementing Niemeyer’s exhibition buildings, joined by a serpentine roof canopy over a connective esplanade, at Parque Ibirapuera in São Paulo.

Burle Marx was also a messenger, an early advocate for the environment – his voice and his speeches were some of his most powerful gifts. As an elite cultural counsellor, he remained close to the regime, perhaps a conservative stance. It should be noted that this authoritarian regime was amply supported by the middle and upper classes in Brazil during its whole existence, certainly by those profiting economically. Burle Marx sought to reconcile the world of the environment with that of the encroaching realities of a rapidly urbanising Brazil – one with a massive housing crisis, with extreme income inequalities and with the marginalised poor scraping the landscape and settling informally on the granite hills of Rio de Janeiro.

We must recognise that these realities, and indeed these human rights, were often at odds with his advocacy of landscape conservation. And what of Burle Marx’s decision to work with the military regime? This must be seen as ethically compromised, though also common to many political contexts and certainly inextricable from the international collusion of countries like the US. As Burle Marx’s younger contemporary, the equally fraught artist Hélio Oiticica, would famously stencil on a parangolé flag, ‘Seja marginal, seja herói’, ‘To be marginal is to be a hero’.

Burle Marx’s prescient depositions and his ‘huge voice’ resonate profoundly today – we might wishfully imagine him as a respondent to Brazil’s current president, Jair Bolsonaro, and his defence of the burning Amazon. ‘Our sovereignty is non-negotiable’, stated the Bolsonaro administration following the G7 summit in August 2019. Half a century ago, in reference to clearing fires perpetrated in the Amazon rainforest by the multinational corporation Volkswagen do Brasil, Burle Marx asserted, ‘You have to understand that it is my obligation to oppose everything that I consider an ecological crime … The sacrifice of nature is irreversible.’

See more / content via: https://www.architectural-review.com